Walter Rattray RICE

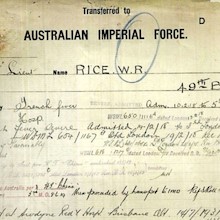

| Rank | Reg/Ser No | DOB | Enlisted | Discharge/Death | Board |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

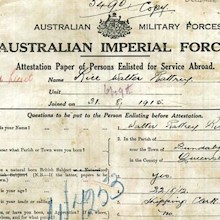

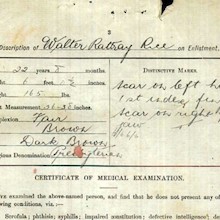

| Lieut | 22y 8m | 31 Aug 1915 | 20 Jul 1920 | 2 |

Lieutenant Walter Rattray Rice

(1892—1931)

Bundaberg-born Walter Rattray Rice was a 22 years old shipping clerk when he enlisted in August 1915 in Melbourne. He served in France and Flanders as a Lieutenant in the 49th Infantry Battalion – including in the Battles of Messines, Polygon Wood and Amiens - and returned to work as a shipping clerk after the War.

However, Walter couldn’t cope with work for long and in 1924 the Repatriation Commission accepted that he had pulmonary tuberculosis as a result of his war service – a condition from which he died back in his home town of Bundaberg in 1931, leaving a wife and two young daughters. He is among the substantial number of people who died because of their war service in the years after the fighting finished. Pulmonary tuberculosis is an infectious disease, and his wife Mary – who had cared for him for many years - died of the same disease three years later, in 1934.

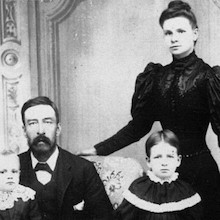

Family background

Walter was born in Electra Street, Bundaberg on 29 December 1892, the eldest child of Walter William Rice (1860-1943) and his second wife, Jane nee Rattray (1865-1957). Walter senior had been born in Weymouth, England and his first wife was Elizabeth née Nixon, with whom he had one daughter who survived childhood. Elizabeth died in 1889 and Walter married Jane in 1891 in Bundaberg, where he was a telegraph line repairer at the time - later he worked as a Postmaster.

Another of Walter senior’s sons – Richard James Rice – also served in the 1st AIF, enlisting in May 1916 and serving with 7th Machine Gun Company. A third son and one daughter died young and there were three other daughters in the family – Florence (from Walter senior’s first marriage), Margaret and Jane (married name Davis).

Early life and enlistment

Walter junior served two years in the senior cadets and then joined the Wide Bay Regiment of the Citizen Military Forces, where he was a Lieutenant from July 1911- June 1912. He worked as a shipping clerk and was presumably working in Melbourne where he enlisted in August 1915, at the age of 22. He was tall in that generation at 184cms, weighed 75kg, and his religion was Presbyterian.

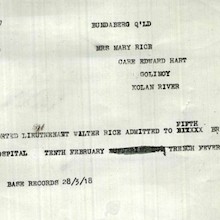

Initially made a Sergeant, Walter was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in March 1916. Later in that year, with embarkation looming, Walter married Mary Harte in St Stephen’s Roman Catholic Cathedral in Brisbane on 6 September 1916. Mary too had been born in Bundaberg, the youngest daughter of Edward Harte, a farmer and Annie née Docksey, and after she trained as a nurse at the Bundaberg General Hospital, Mary volunteered and was placed as a sister at the Military Hospital in the Brisbane suburb of Enoggera. With marriage approaching she resigned from that position in August.

Walter embarked in Sydney on the HMAT Ceramic A40 on 7 October 1916 - disembarking in Plymouth, England on 21 November 1916. After attending an Officers Course of Instruction he proceeded to France in March 1917 where he was formally ‘taken on strength’ with the 49th Battalion.

Flanders and France

In March-April 1917 the Germans were staging a withdrawal, but they fought hard as they went. Soon after Walter arrived the 49th captured railway cuttings on the Cambrai to Arras line, and then prepared for the major Allied attack at Messines in June 1917. Messines was a victory - but a very costly one - and the 49th suffered casualties of 12 officers and 367 men. Walter survived and was promoted to Lieutenant after the Battle.

In September 1917 the 49th including Walter took part in more ferocious fighting in what was named the Battle of Polygon Wood. Early in February 1918 Walter fell ill and in the 3rd London General Hospital in Wandsworth he was diagnosed with severe trench fever.

Historian David Noonan has written about the conditions in France and Flanders:

…where men were forced to wade knee and thigh deep in a cesspool of filthy water that filled the trenches. The smallest scratch could turn septic, with one of the very real consequences of trench feet being gangrene. Septicaemia killed men in the absence of antibiotics…Fevers raged through the ranks, leaving medical officers overwhelmed and not even sure of the origins of these fevers.

It was May 1918 before Walter had recovered sufficiently to be discharged to a depot, and 7 August 1918 before he was able to re-join the 49th in France. The next day the Battalion took part in the Battle of Amiens, when the Allies launched their own major offensive - which was successful and the beginning of the end for the German Army.

The last action for the 49th was providing part of the 4th Division’s reserve for the attack on Hindenburg outpost line in mid-September 1918.

Walter returned to the UK early in March the following year, and left on the HT China - arriving in Melbourne in June and being discharged on 20 July 1920.

Post-war

On return to civilian life Walter and his family resided at 206 Donald Street, East Brunswick and Walter worked as a shipping clerk for McDonald Hamilton and Co., at 467 Collins Street, Melbourne.

Late in November 1920 he had a recurrence of trench fever, with headaches, shortness of breath, pains in his hip and back, and a slight palpitation of his heart. Although he made some recovery his health was in decline, and in November 1923 he was admitted to the Caulfield Military Hospital and eventually diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis In June of 1924 the Repatriation Commission accepted that this condition was caused by his war service and granted a full pension.

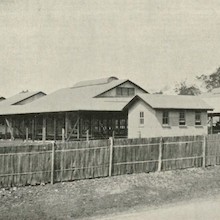

Walter had further periods of hospitalisation late in 1927, and in the middle of 1928 he and Mary moved back to their home town of Bundaberg. There he was attended by Dr Duncan Fowles (also on the Honour Boards). The disease worsened and Walter spent much of the first half of 1930 confined to his bed, until Dr Fowles recommended to the Repatriation Commission in August that Walter be admitted to a sanatorium. Walter was subsequently nursed in the Rosemount Repatriation Hospital, and then the Ardoyne Red Cross Home in Corinda. It was in Ardoyne that he passed away on 31 July 1931, attended at the last by Dr D. G. Croll (also listed on Honour Boards). His remains were buried the next day, with Roman Catholic rites, in the Toowong cemetery.

Walter was survived by Mary and his two daughters (Lillian Constance and Patricia Margaret Veronica). Pulmonarytuberculosis is infectious and Mary also died of the disease in 1934 - her remains rest in the Roman Catholic cemetery, Bundaberg.

Another sad postscript is that Walter’s younger brother Richard James Rice, who had also served in the 1st AIF, died in November 1922 in the Rosemount Repatriation Hospital from the repercussions of the appendicitis and hernias that he suffered during his service. One can only imagine the grief for the parents who saw their two adult sons die in the circumstances they did.

In a detailed study published as Those We Forget in 2014, historian David Noonan has challenged as too low the commonly used figure of 60,000 Australian WW1 dead, also making out a case that when regard is had to war-related deaths in the 20 years after WW1, there were at least 70,400 service-related deaths of people who served in the 1st AIF. Walter and Richard are among that higher number - and then there is the tragedy of Walter’s wife Mary. So many long days and short years for the three of them.

Lest we forget.

Written by Ian Carnell AM, Buderim. July 2017. Additional images added by Miriam January 2025. ©

SLQ Historypin – Linking our digital stories to the world.

The Lives, Links and Legacy Stories are being shared through the State Library of Queenland's QANZAC 100: Memories for a New Generation Historypin Hub. Visit this site:

Know anything about this person or want to contribute more information?

Please contact Miriam at staheritage@gmail.com